Research Example: Playtesting

Background

Although I also used other methods like usability testing or surveys to answer different questions about Destiny, playtests are the bread and butter of gaming research. In a nutshell, playtesting is a form of multi-user simultaneous testing that involves playing a game, where each participant sits at an identical station where they have everything they need to play the game and to provide feedback (usually a survey format). Playtests are typically about measuring the “fun” of a game, and identifying any blockers to fun such as gameplay being too challenging or too easy, players feeling lost or confused, and other issues. Most playtests I did had between 15-36 participants, where up to 18 could test simultaneously in our lab.

Note: Nondisclosure Agreements are serious business. All in-development product images and other artifacts from my research are confidential to Bungie. I will not be sharing real raw data, photos of real participants, real examples of reports, or examples of impact that include content or features that did not ship in some form.

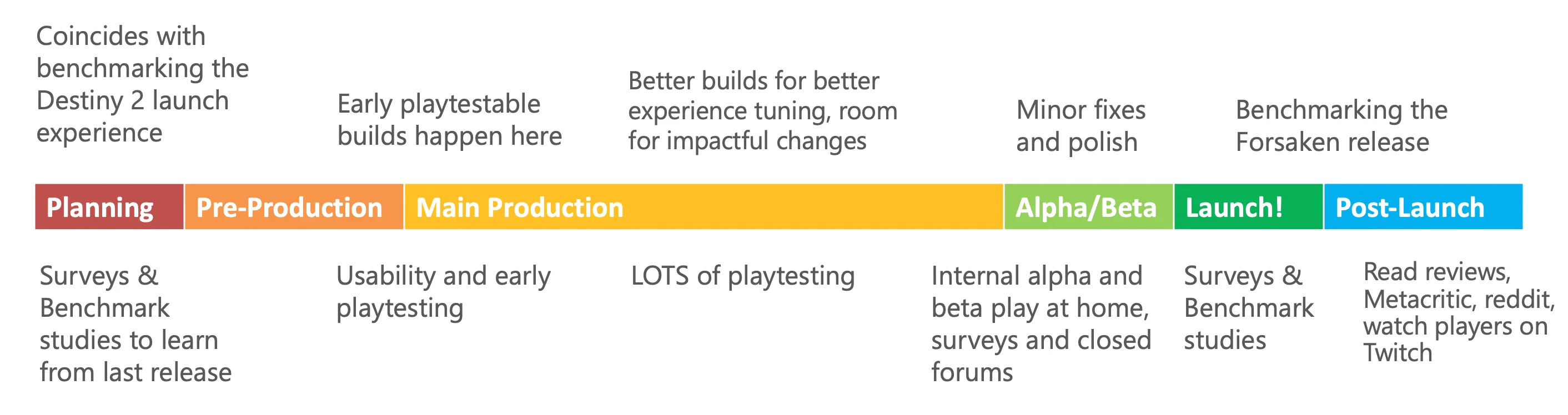

Forsaken’s development cycle was roughly a full year and I led the research strategy on Forsaken for the duration. Planning for the Forsaken expansion started right around the same time as the launch of the base game of Destiny 2, with the intention of releasing the expansion after Destiny 2 had been out for about a year. Playtesting started once we had builds that felt roughly representative of the intended play experience.

Problem

We needed to understand how this major expansion was performing during development and how it compared to the previous release. Are the missions too hard or too easy? Do people understand their goals? Do they get lost in the missions? Do they like the story? …Is it fun?

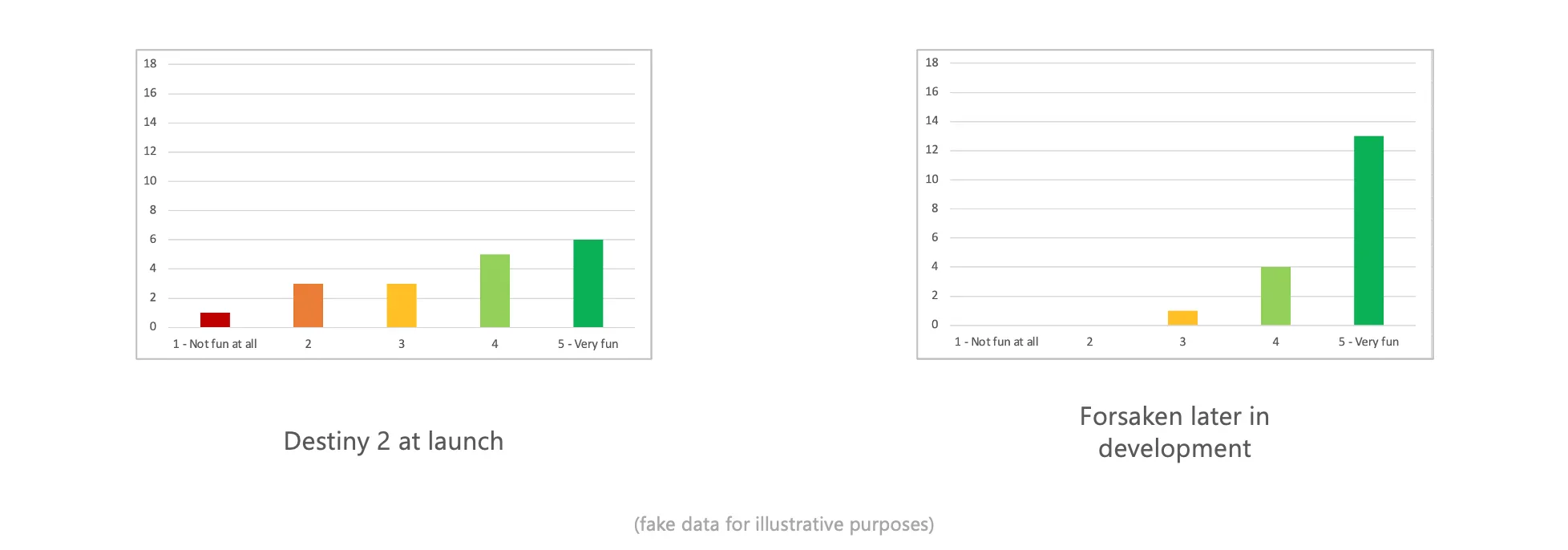

The problems you see here are pretty consistent throughout the game development process. This is something that is typically tracked iteratively throughout development to make sure we’re getting things right. In the case of Forsaken, it was very important that we got it right, because the original launch of Destiny 2 did not quite land as well as we hoped, and Forsaken was our critical chance to turn things around.

Example Research Questions

- How much fun is each mission or activity? What do they like and dislike?

- How difficult is each mission or activity? What is too hard?

- Are the player’s objectives clear or confusing?

- Do players ever feel lost? If so, where?

- What do they think about their character’s abilities, guns, and gear?

- Do they feel powerful?

- Do they like the more serious, darker narrative?

Methodology

Participants: I evaluated this expansion with about 15-18 people per playtest who had played the original Destiny 2 campaign. Because I was evaluating an expansion to the game, players would have completed the original campaign prior to starting the new content.

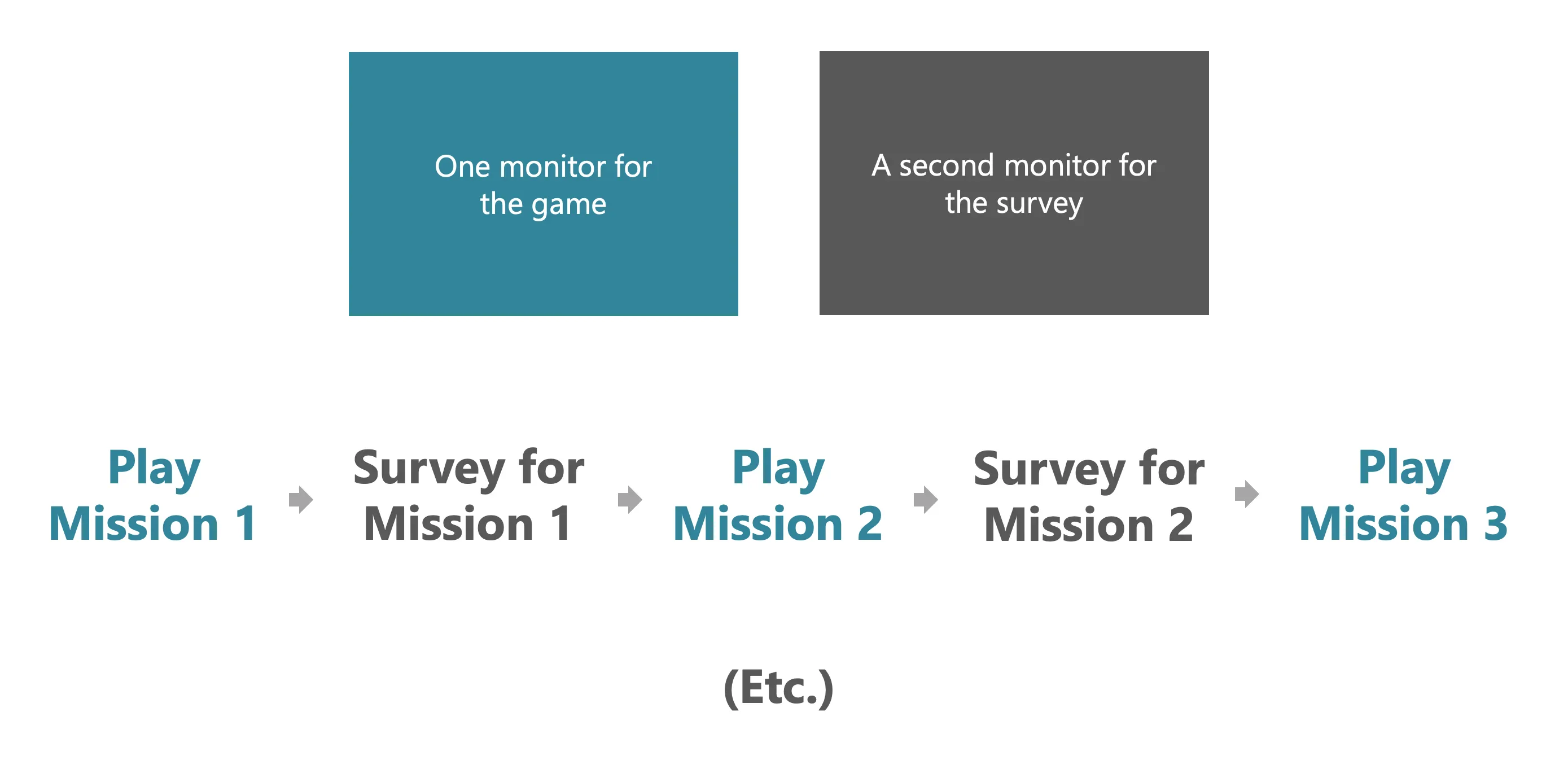

Most playtests are designed in a way that lets all the participants self-pace through the content using a survey on a second monitor at their station, with questions to answer at certain points. For example, the survey would instruct them to play mission 1, then to click next when they’re done with that mission. They complete the mission playing on the other monitor, hit next, answer some questions about it, and then the survey tells them to play mission 2, and so on until they get through all of the content.

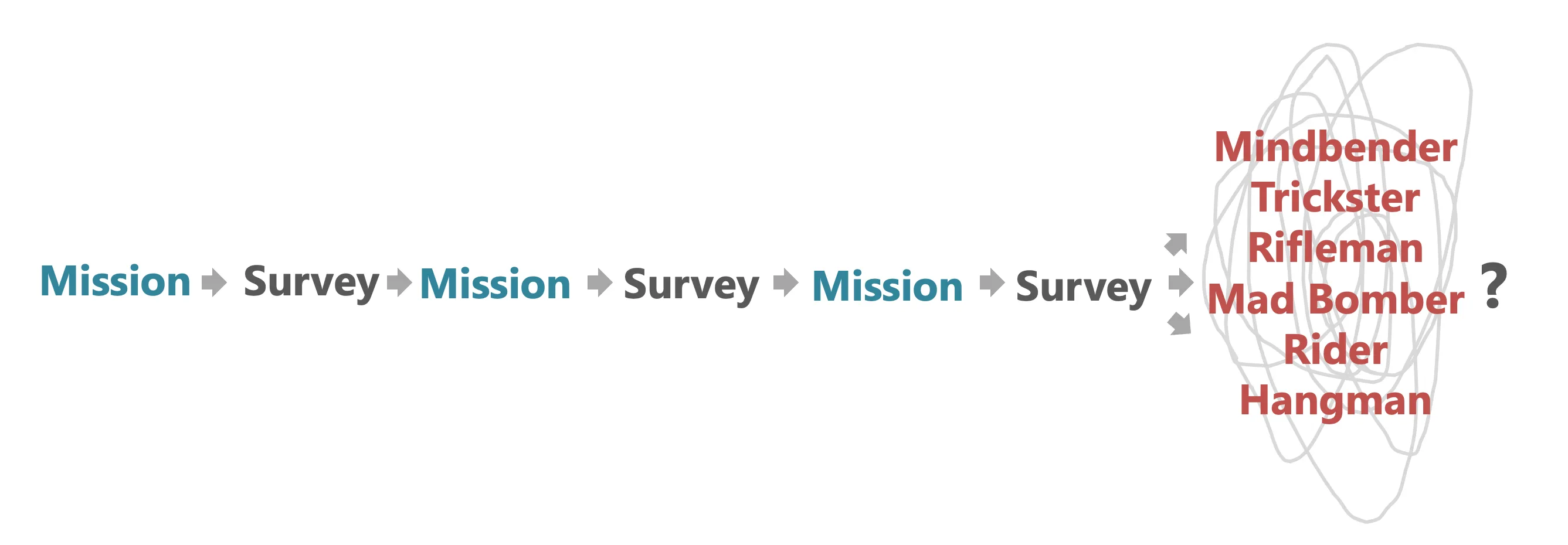

This usually works for a game story mode, but Forsaken’s new campaign presented a challenge to this method. Right in the middle of the story, your Guardian (your character) is tasked with hunting each of Uldren's Barons down on the Tangled Shore and defeating them one by one. But at one point fairly early in development, it was decided that players would be able to play 6 of those Baron missions in whatever order they wanted. The Tangled Shore was now wide open for players to roam free.

Suddenly the campaign became non-linear after the first three missions. Normal playtest structure for a story mode is typically linear, so the traditional playtest structure for a story mode wasn’t going to work. I could have taken two different approaches here...

I could make the players find and defeat each Baron in a specific order and then do specific surveys for each activity – basically forcing the game to fit the usual methodology. Or I could allow the players to choose the order of the Barons, which was more in line with how the game was intended to be played, but just have one set of questions about the overall Baron hunt experience at the end of those 6 missions.

There are pros and cons to both of these. More surveys meant more specific feedback about each mission, but it’s not representative of the intended experience. Having one survey at the end meant I would be measuring something much closer to the real player experience, but with less depth of feedback for the missions.

But usually the point of doing research is to answer specific questions. To inform the product. To help make decisions. So I sat down with the campaign design lead to weigh these tradeoffs and figure out what was most important and useful for him, so I could give him what he needed to make decisions about the game’s direction. Together we decided on the second of the two options. Players could roam the map freely and take out the Barons in the order of their choosing, just like the intended gameplay experience, and focus on giving more general feedback across the whole Baron hunt, rather than dive in deep on each one.

This was also a better testing experience for my participants, because fewer breaks for surveys means less potential for survey fatigue and more play time. Keep in mind that in the case of testing an entire story mode such as this one, participants spent two full days playing games and taking surveys! That's a large commitment, and a lot of survey questions.

Data and Analysis

This playtest resulted in a large amount of data to analyze and report on, a mix of qualitative and small-scale quantitative data.

| Quantitative Examples (mostly numerical ratings) | Qualitative Examples (mostly open-ended questions) |

|---|---|

| How easy or difficult is this mission? | What was difficult? |

| How fun is this mission? | What did you like / dislike about this mission? |

| How often did you feel lost? | What part of the mission did you feel lost? |

| And some fun heatmap analytics data, too! | And notes from researcher observations! |

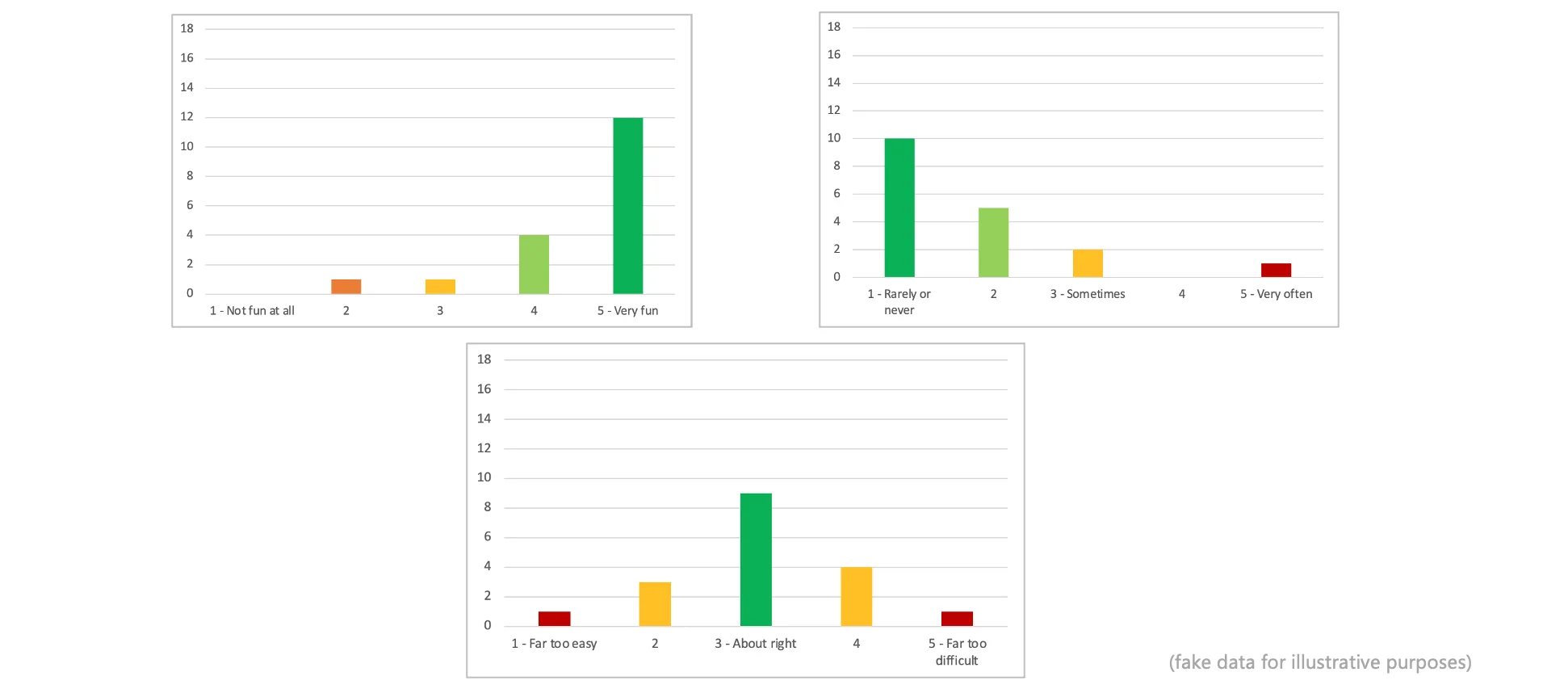

Most of the quantitative data resulted in some basic distribution graphs and averages – for likert-scale questions like how challenging the mission was, or how much fun, or how often they felt lost. I also generated some heatmaps with the analytics data that were collected directly from players’ gameplay, including things like the coordinates on the game map of where a player character died, what killed them, with what weapon, etc.

The qualitative open-ended responses were coded for themes and noteworthy anecdotes, and researcher observations were reviewed for usability issues and bugs that I or my research assistants might have noticed while watching people play.

Outcome

A few specific examples of impact that came out of this particular playtest included:

- Difficulty tuning: Helped the designers dial in various things over time that affect challenge, so each mission was fun, not frustratingly hard and not boringly easy.

- Indicators of Challenge: Visual indicators of Power level requirements for each mission, activity, and bounty were added to help players understand if they had leveled up enough to play those activities instead of going in without knowing they were under-leveled, having a frustrating experience, and quitting.

- Awoken Talisman Quest: The team removed the “Heroic” requirement for the Public Event (effectively a hidden objective) and reduced the number of defeated Taken needed to charge the Talisman (too many = tedious).

- New Weapons System: Changes to the weapons system took the best of D1 and D2 and expanded upon it, so the playtest needed to validate the changes and evaluate perception. Players figured out how it worked and they loved it. A lot of players liked the new bow archetype, too!

For playtests I thought about success in a few different ways.

Individual scores within a single playtest evaluate specific aspects of the game (e.g., a “fun” score of 4.2 out of 5 was moderately high). Something like how fun a mission was or how much they liked the story should ideally be high, frequency of feeling lost when navigating the level or confused about their objectives should be low, and challenge should be right in the middle. Basically we want to see a lot of green here, and identify what’s causing the orange and red so we can fix it.

When tested repeatedly throughout development, those types of scores should either increase over time (more fun), or move closer to the center (difficulty is not too hard and not too easy), or decrease (rarely/never feeling lost) as issues are identified and changes are made across the builds. It’s not unusual for early builds to not feel very fun. Encounters may not feel polished or might feel repetitive, enemies might be way too hard, waypoints might be inaccurate, the goal of the mission might not be clear, terrain might be challenging to navigate – these are all things that can be pulled out of the follow-up questions after each rating where players are asked to describe what they didn’t like, or what felt too hard. If we identify and address those things, the ratings will improve over time.

Lastly, it was critical for us to improve upon the first release of Destiny 2. I was also able to compare the Forsaken playtest data against the same types of measurements from Destiny 2, because I had done UX benchmark playtests of the original campaign at Destiny 2’s release as well as a larger scale survey via email of players who bought the game and completed the campaign within the first couple weeks after launch. So I had the same measurements for Destiny 2 – things like fun, amount of challenge, what they thought of the story…And thankfully, Forsaken appeared to be scoring well against it.

And basically, it got more fun each time I playtested it, and ultimately it was on track to be better than the Destiny 2 release.